Guest post by David Kosub

*** Please note David is only a citizen historian and apologizes for any incidental fake news. He hopes neighbors share these stories and are inspired to write about their community in the new year too.*** [Ed. Note: If you would like to contribute a blog post to Next Stop . . . Riggs Park, please send an email to nextstopriggs@gmail.com]

Back in 2011, all around the DMV, we found ourselves asking, “What is NoMA anyways”? After Amazon made its announcement, we found ourselves wondering something similarly–“National Landing, really”? I guess it’ll be called NaLa soon enough.

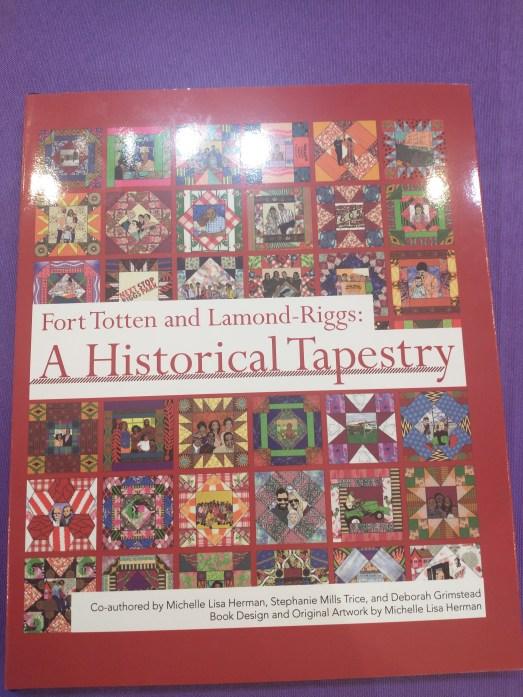

Even closer to our “scrappy, down-home” neighborhood, if you want to see sparks fly, then ask someone about what they think about the name “Fort Totten Square,” or about their initial impressions of “Fort Totten” metro. But, be careful. Make sure you do not call it Fort Totten-Riggs station though. For that matter, where did the name “Lamond-Riggs” come from anyways–or as I call it, LaRi?

Here, in this two-part series, I sought to uncover this mystery and meet the elusive Lamond and Riggs. In Part 1, let’s start by turning the clocks back about a century and a half and meet the Lamonds.

Terra Cotta Warriors: A Different Type of Baked Earth in Washington

There is a silty, reddish clay earth right beneath your feet. This soil, the bane of many area gardeners – like yours truly – who just want to grow some darn tomatoes and peppers in their yard, actually contributed to a vibrant industry over a century ago. Heating this ample clay-ground proved perfect for making a certain material commonly found in sculptures, flower pots, pipes, bricks, roofing tiles, and even metro platform embellishments.

And, voila, the Terra Cotta neighborhood was born. The Federal government officially recognized this description in 1979, the same year as the names Lamond-Riggs and Fort Totten Park, and it still existed as recently as 2007.

This name is linked to a thriving business established here in the latter half of the 19th Century, the Potomac Terra Cotta Company. Its impressive, large ovens could be seen creating clay tiles on the eastern side of the recently laid Baltimore and Ohio train tracks, near today’s Van Buren Street, Underwood Street, and Chillum Place.

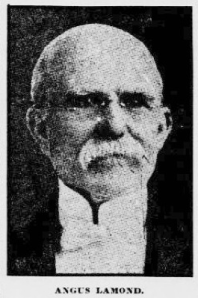

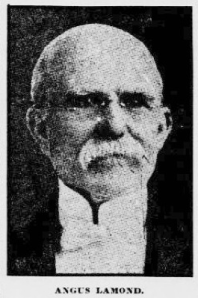

Picture of Angus Lamond

Drum roll please, this company was the brainchild of one Scottish-born Angus Lamond. He started the company some time after immigrating to the United States at the age of 25. With Gaelic and Norse origins, his family name meant “the law man” and was llikely pronounced “Laumon.” If you cannot get enough Game of Thrones, check out this actual ancestral history of the Lamonts of Tiree, from which our hero Angus may have derived.

In 1873, officials with the railroad, specifically the Metropolitan Branch rail line, moved the nearby Brightwood station closer to the company, renaming it Lamond Station or Terra Cotta. Likely located somewhere between where Fort Totten and Takoma metro stops are today, the relocation of this simple, three-sided wood-framed structure caused some consternation. The railway thus justified the move by explaining that the station was better protected from vandals at the new site.

Advertisement for Potomac Terra Cotta Company. Source:

The new station served another role too, incentivizing people to move to an unincorporated parcel of land destined to be a nuclear-free, suburban oasis located “high above the swampy, malaria-ridden Washington City.” When Alcena Lamond, Angus’s better half, encountered it in 1875, she lamented that the area “was all that a wilderness could be.”

Even with the fear of the unknown, the Lamonds would come to embrace the wild. The town would grow without regard for jurisdiction, incorporating part of the large Riggs estate (but we will get to Riggs later in Part 2). By 1889, this “place only for the wild creatures of nature” expanded from the original 5 homes—one of which was the Lamonds—to over 200.

The call of the wild was so strong that Angus and Alcena even donated land for a library, though not likely the one you are envisioning. Angus allegedly convinced his childhood friend Andrew to give a $40,000 construction grant, which together with the land, eventually became the Takoma Park Carnegie library in the early 20th century. Before it could become reality, the contribution of the “best men” in Takoma Park needed to testify at a House hearing in 1907, including Angus who was glorified as one of the “most generous” and “prominent” citizens during the lovefest. A Congressman touted the library would be a “valuable addition to the educational facilities of the District of Columbia . . . [and] that the remoter sections of the District are entitled to the largest possible use of the Washington Public Library.” Let’s keep that in mind as our local branch gets its own upgrade over the next couple years!

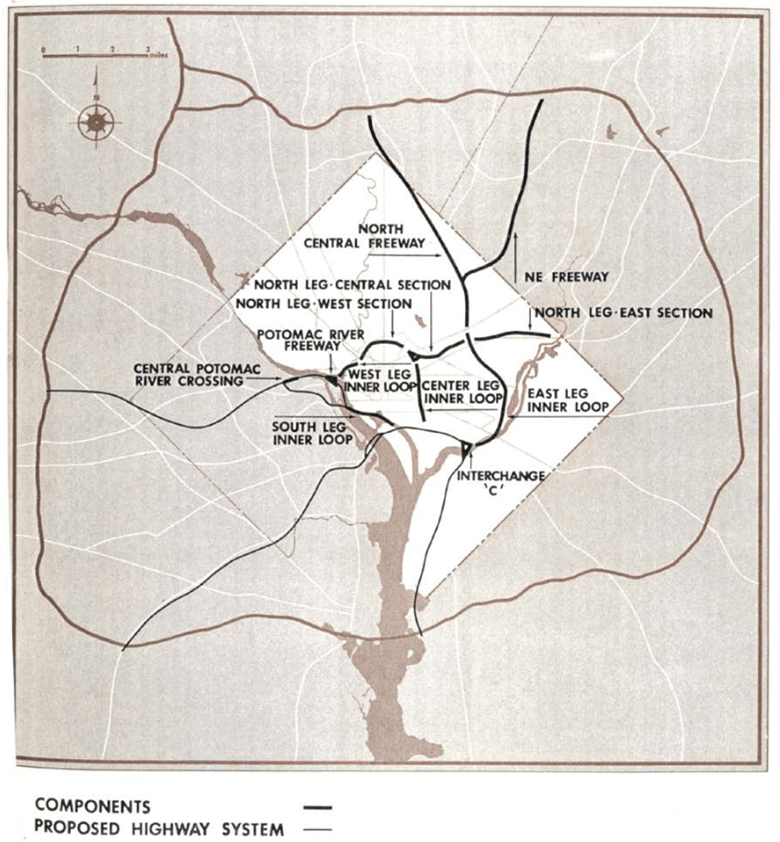

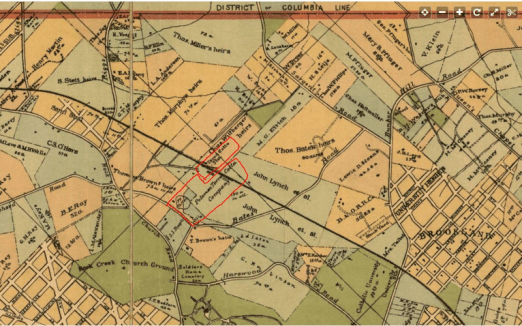

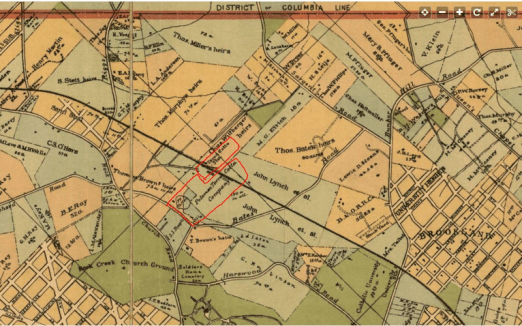

1890 map of Terra Cotta neighborhood. Company and railroad are circled in red Source

Alcena, the true rock star she was, worked her magic on the 57th Congress to pass legislation in 1902 to incorporate the Eastern Star Home for the District of Columbia. This institution was a home for “needy and worthy [fathers, their widows and orphans, and members] of the Order of the Eastern Star of [the District of Columbia].” The Order of the Eastern Star is a Masonic group (complete with its own International Temple in Dupont) that recognized her as a Grand Matron in 1896. Angus was prominent in Masonic circles too, recognized as a Grand Patron. The Eastern Star Home, essentially a nursing home off New Hampshire Ave NE, naturally (being D.C. and all) was destined to be a future sight for a zoning fight between the District, neighbors, and developers over a century later.

Meanwhile, back at the Terra Cotta Plant, work was seemingly difficult producing those clay tiles. For starters, it claimed the life of one of their sons in a tragic clothing-related accident in 1922. The other son also lost an arm while working in the factory. But, despite this incident, this son would successfully manage the company for decades until its closing in the mid-1950s (so, give him a hand for that, he needs it). Some of their clay fixtures can even probably still be found on houses in our neighborhood today.

Angus, who died in 1917 around the age of 75, and Alcena, who died in 1932 around the age of 82, both now leisurely hang out right around the corner in Rock Creek Cemetery (Section R11, Lot 49, Grave 3 and Grave 1, respectively). They are just a 25-minute stroll from the community bearing their name, so pay them a visit.

Train Spotters (caution ahead)

For an additional, unfortunate twist of fate, the Lamond/Terra Cotta station is known for the worst train disaster in Washington D.C. history, one hundred years before the one you are likely thinking about. This accident was later recounted in the book Undergraduate Days 1904-1908 as a “terrible noise…of an explosion, escaping steam, breaking wood, groaning brakes and human screams” heard as far away as Brookland and Catholic University. A newspaper recounted that “the butchery of the passengers was one of the most frightful things in the history of railroading.” They were cut into pieces and portions of their bodies scattered all along the track. When all was said and done, 53 passengers lost their lives, over 70 were injured, and none of the engineers on the offending train were found guilty of manslaughter.

Image of newspaper article on train crash

A citizen historian who spent 10 years studying the crash opined that this incident “hastened the conversion of passenger cars from wood to steel and led to improvements in railroad signaling,” so I guess there is that silver lining. Though if you need another pick-me-up right about now, as I did when writing this, then see this happy story about the Fort Totten metro train tracks before going to bed.

So, that was the Lamonds. Stay tuned for Part 2 of our naming saga in which we’ll learn about bankers, emancipation, and dictators, oh my . . .