By Gavin Baker (Guest contributor)

As the Commemorative Works Technical Assistance Program is soliciting ideas for important events and figures to memorialize in Wards 4 and 5, it’s a good moment to reflect on the freeway revolts and their impact on Lamond-Riggs and surrounding neighborhoods.

Post-War Context

The District’s population, both Black and white, boomed with the expansion of federal government and military jobs during the New Deal and World War II. The 1950 Census recorded DC’s highest population ever, more than 800,000, a number it has yet to reach since.

With the demobilization following WWII, more resources became available to build new housing for that booming population. In June 1950, the first ads appeared in the Washington Post and the Evening Star for a new development: “Live better… and more economically… in beautiful Riggs Park, Washington’s newest Subdivision!” The ads highlighted the offer for veterans to buy a house with just a $50 down payment.

The suburbs boomed, too, and in the 1950s, DC’s population underwent major changes. In 1950, the city’s population was 65% white; by 1960, it was 54% Black. The 1960 Census showed the first decline in the District’s overall population in its history, which would continue for each of the next four decades.

White flight to the suburbs was driven by both racial and economic factors, one of which was transportation. Automobile usage swelled: in the 1950s, American auto manufacturers sold one new car for every three residents. To serve them, U.S. governments embarked on efforts to extend and widen roads, including an influx of federal funding under the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, signed by President Eisenhower.

“White Man’s Road thru Black Man’s Home”

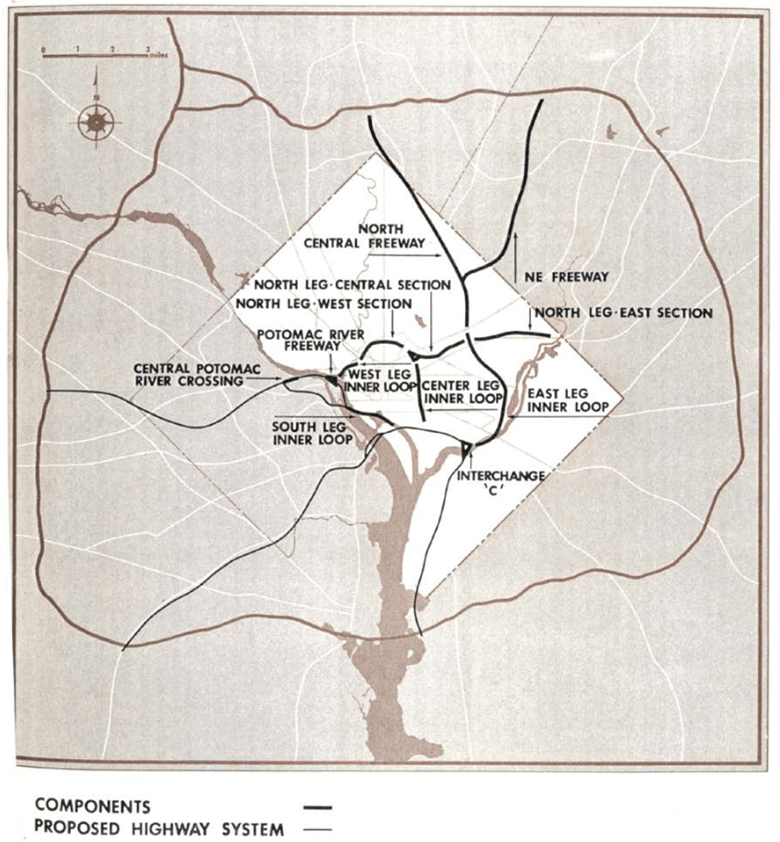

Against this context, officials developed plans to expand freeways in DC, which protesters would come to deride as “White Man’s Road thru Black Man’s Home.”

In Wards 4 and 5, planners aimed to build the North Central Freeway through neighborhoods such as Brookland, Michigan Park and North Michigan Park, Lamond-Riggs, and Takoma. Fort Circle Park would have been paved over to become the Northeast Freeway. If these plans had succeeded, today our neighborhood would be a highway interchange.

They didn’t succeed – because of the freeway revolts. A multiracial coalition of activists banded together in the 1960s to oppose the destruction of neighborhoods, the pollution that would result from the freeways, and the prioritization of (largely white) suburban commuters over (largely Black) urban residents. The freeway opponents, by and large, won: most of the planned freeways, including the North Central Freeway and the Northeast Freeway, were never built. By the 1970s, the remaining plans were formally withdrawn.

Lamond-Riggs is not merely a footnote to this history. Simon Cain, president of the Lamond-Riggs Citizens Association, served as the first chair of the Emergency Committee on the Transportation Crisis, the focal point of opposition to the freeway plans.

The freeway revolts were a watershed moment for racial and environmental justice in DC. If the freeways had been built, our neighborhoods would be radically different, with more traffic, more noise, more pollution (and related diseases like asthma), and more disinvestment. Lamond-Riggs would be somewhere to drive through, rather than somewhere to live.

There were other notable consequences of the freeway revolts. The protests were a launching pad for future leaders, including Marion Barry (who would later serve as Mayor of DC) and Sammie Abbott (who would later serve as Mayor of Takoma Park). In addition, the revolts led to the creation of Metrorail as an alternative to freeways. Today, Metro’s Red Line parallels the planned route for the North Central Freeway, serving Brookland, Fort Totten, and Takoma – without having paved them over.